Some nights in Manila do not end, they simply change their skin. The streets breathe differently after dark—with traffic slowly waning, shadows and darkness blanketing every corner and crevice, and neon humming like a secret only the city knows. In those hours, the world feels both alive and dangerous, holding space for stories that rarely make it to daylight.

For Petersen Vargas, these nights were not just backdrops but a mirror that stands as a reflection and witness to his own becoming. It is the pulse where memory and desire first learned to speak. With Some Nights I Feel Like Walking, he returns to them not as a tourist scraping for postcards for nostalgia but as a soldier unafraid to carve the truth of his queer identity into cinema. What unfolds is more than a film but a confession, a ballad, and a love letter to a city that bruises as much as it embraces.

Vargas has never walked a straight path, only one that winds through unexpected turns and reinventions. His breakthrough with 2 Cool 2 Be 4gotten carried him from the intimacy of festival screens to the wider reach of mainstream distribution. He then stepped into the digital era during the pandemic, a time of global standstill, with Hello Stranger, finding resonance in the Boy’s Love (BL) wave and proving that tenderness could thrive online. Later came A Very Good Girl, his bold leap into the grandeur of Star Cinema, where he worked at the heart of the industry’s well-oiled machine. But it is in Some Nights I Feel Like Walking that Vargas circles back to where he began, not bound by the binaries of “indie” or “mainstream”, but anchored in something more organic and true.

Here, he is not a director for labels or markets, but a storyteller who has chosen, finally and fully, to tell a story that feels like his own skin.

“I wanted it to be more ‘present’, and [tell] the immediate stories that I was experiencing being someone who has already been living in Manila. So, from the ’90s Pampanga coming-of-age, now I wanted to tell the present day in Manila and how I wanted to see it and experience it. And then, so now, the questions begin: Ano yung gusto kong ikuwento about Manila? And whenever I talk about this film, I always say that it’s my ode to the streets of Manila, because I owe it to the streets of Manila for birthing my queer identity.”

Long before cameras rolled, his latest opus had been living inside him. As a teenager walking Manila’s nocturnal veins, Vargas remembers cruising, meeting strangers whose faces blurred with the sunrise but whose presence left indelible marks. From those encounters emerged notions of both intimacy and impermanence—the duality he longed to capture. But Some Nights I Feel Like Walking is not just a diary entry. By setting his story against Duterte-era Manila, a city scarred by violence and surveillance, Vargas threads memory with politics.

A single night, a dead friend, a brotherhood bound by grief: the film asks what survival looks like in a city that both births and brutalizes.

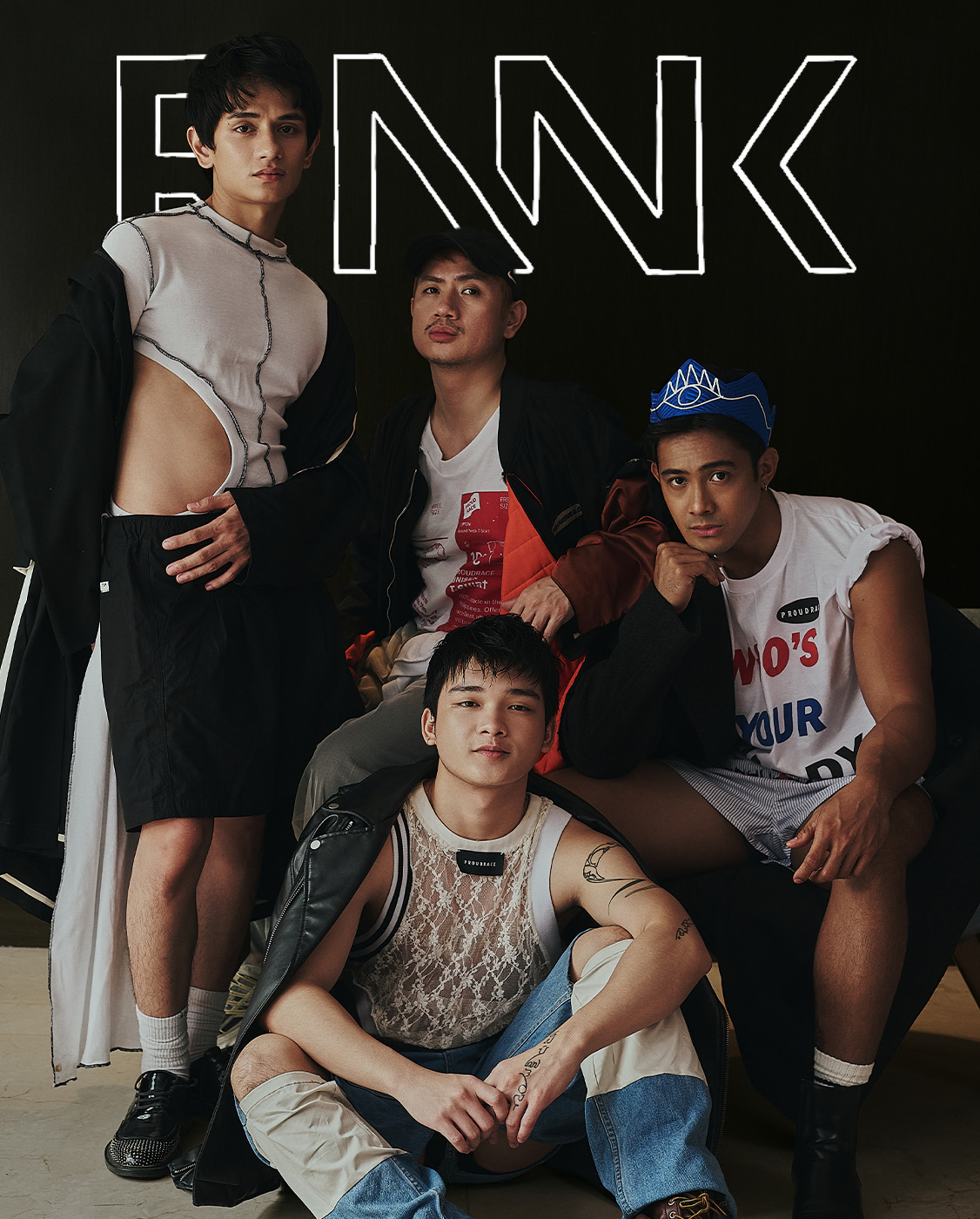

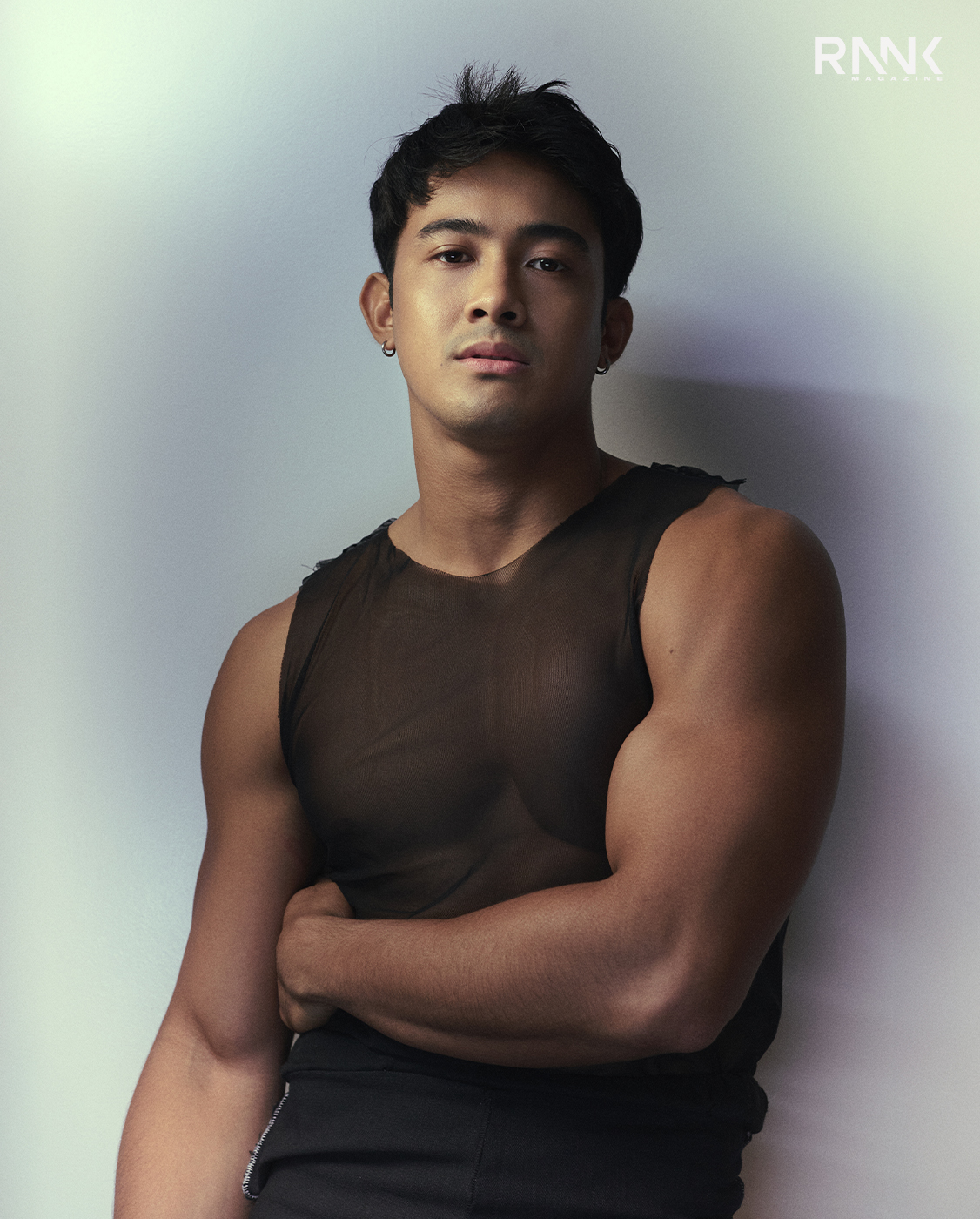

Stitching a piece as vulnerable as this is not a one-man show. Along the dimmed streets of Manila, Vargas walks with five more boys. To tell it authentically, he obsessed over casting. Two years and hundreds of auditions until, finally, the right chemistry clicked. Vargas likens it to building a boy band, except this debut wasn’t choreographed under strobe lights but under the flicker of street lamps. “Kailangan maging totoo yung brotherhood,” he insists, because without it, the story collapses. This authenticity extended to his directing style.

“[Madali] siya in terms of what I wanted to see, ‘cause I feel like this is more autobiographical than my first feature. ‘Cause in my first feature, I did not write it. This one, I wanted to write, ‘cause I wanted it to be told and based on my own experiences, from my own heart. So, madali yung part na ‘yon, and ang mahirap is how to get it made.”

Of the lead cast staking this claim, musician turned first time actor Miguel Odron, recalls his journey to and with his character, “I would ask P (Vargas), ‘What [would] Zion do in the script?’ And then he would tell me, ‘Well, that’s not my job. That’s your job,’” blurting out with a light laughter. “So, you really have to show up.”

That freedom pushed the actors to carve their characters deeply, grounding them in the film’s beating heart: brotherhood born out of survival. The boys in Some Nights I Feel Like Walking are not just archetypes of how they are described on paper. They are living, breathing fragments of the city, tethered to one another in ways only those who’ve endured together can understand.

As Odron describes realizations while in the process of filmmaking, “You have all these different hands with all these fingers in the pot, and if one of those fingers is out of place—the whole thing could fall apart.” So, when chosen to play Zion, a runaway who was foreign to all the horrors and shadows of Manila nightlife, it came natural to him to flesh out a character that carries a multi-dimensional story.

Odron carefully positioned him within this group of boys who were much more accustomed to the spaces and corners that surround them. He shares empathy to Zion’s personal life terrors while not soaking in too long. He divulges, “You want to lean into the pain so much. But Zion also has these other aspects to him, like his sense of exploration and discovery.”

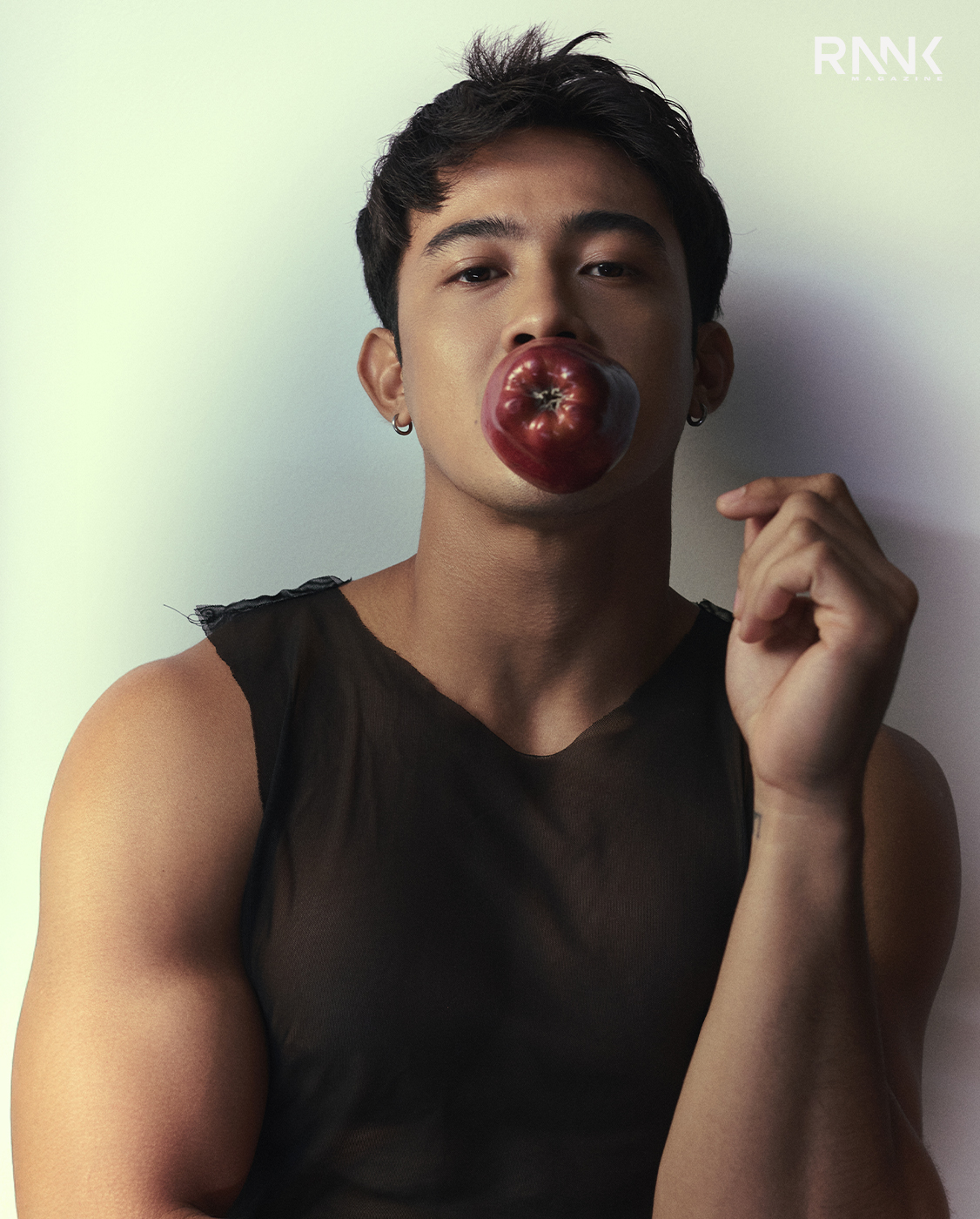

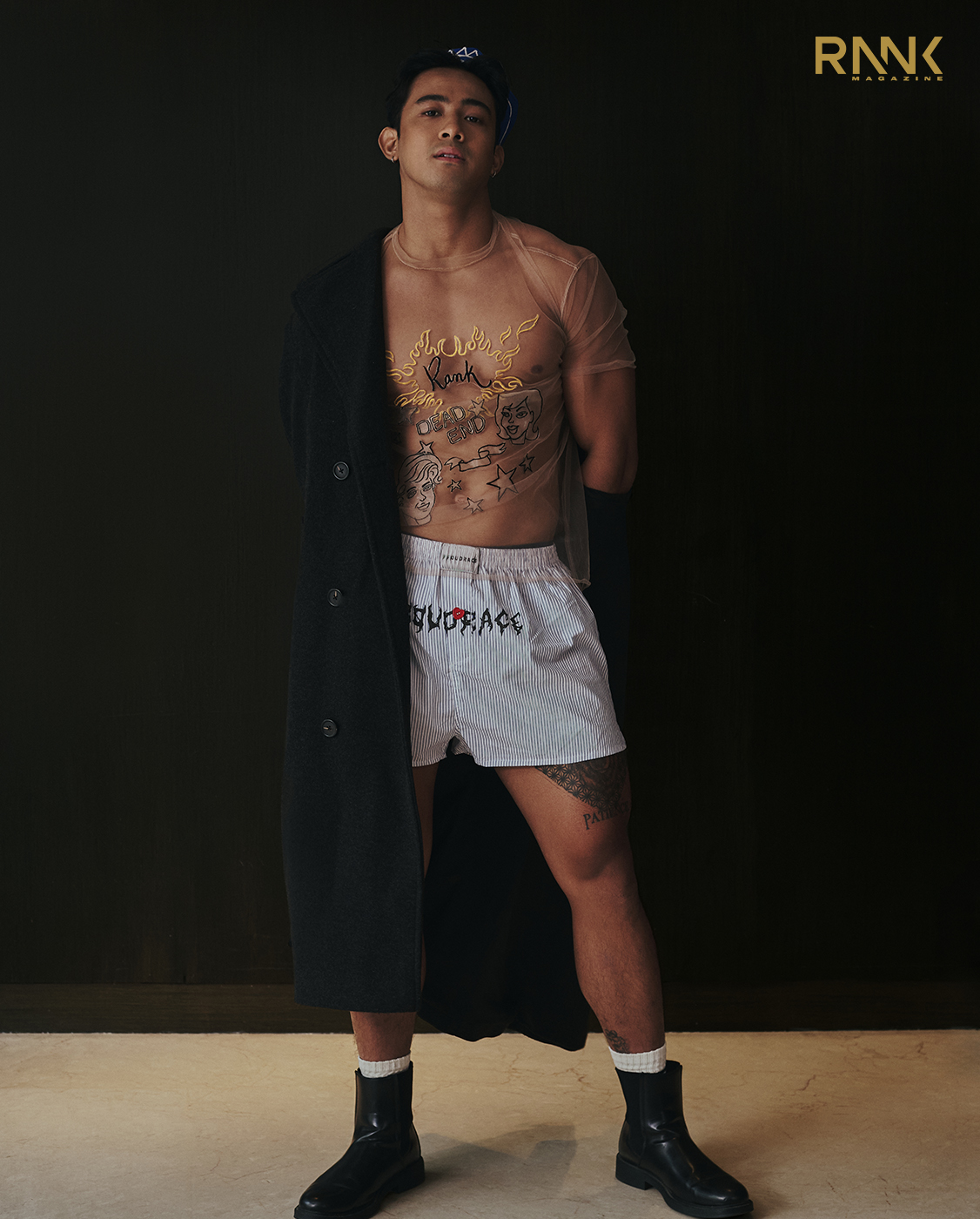

Just like his character Bay/Bayani, reality television graduate and now TV actor and Internet Boyfriend, Argel Saycon is not new to the noise of the streets and the voice of the queers. This sense of normality made it easier for him to engage in a material that touches on queer experiences. “He resonates with me so much because underneath it all, he is this overprotective brother to the group. Ganun din kasi ako sa mga pinsan at mga kapatid ko. Yung mga ginagawa lang niya ang hindi kami pareho. Si Bayani kasi, pisikal siya,” he discloses with a chuckle. This very description goes the complete and polar opposite of how his fellow cast members and the team that worked with him in the film calls him almost unanimously as this “gentle giant.”

With a familiarity with the milieu in his arsenal came a preparedness compounded with and by a great help with his collaborators in what is his first ever venture into a dramatic role for films. “Ang natutunan ko sa mga workshops is to never judge your characters. Wala naman kaming pinagkaiba, kundi yung mga ginagawa niya at mga choices niya. So, kung queer character man or kung stories pertaining to characters of the LGBT community, ang goal naman lagi is to find the best way you can to tell their stories. Gaya nga ng laging sinasabi ni Tommy (pointing to his co-actor), ‘Gawin mo lang.'”

Meanwhile, Tommy Alejandrino owes it to the script. As he plays the role of a sex worker, he is also walking on the edge of endangering the character to sensationalism and perpetuating stereotypes. But the material gave them space to venture beyond these risks, transcending the foreground of queerness and sex work are the stories of camaraderie, brotherhood and a sense of home and belonging. “I was already ‘sold’ sa concept pa lang. I always wanted to do queer films, queer stories and queer roles lalo na to kasi the queer stories that I got to do before are usually very cutey, highschool, BL, which is fun. But this one is a queer story but isn’t too romanticized and commercialized so I felt strongly in being part of this space we are holding.”

On his role as Rush, he furthers, “Madali na rin for me hanapin hindi lang kung sino siya bilang sex worker pero sino siya sa barkadahan nila. Kasi besides them being hustlers, they’re also like a group of boys who found family with each other.”

Perhaps what makes Vargas singular is his philosophy: hailing from a breed of filmmakers uninhibited by notions of “branding”—in being boxed as “indie” or “mainstream.” At the time of production, a long storied decade since the material was birthed from a germ of an idea, by day, he was directing Kathryn Bernardo and Dolly De Leon in A Very Good Girl, by night, he was on the Some Nights set, chasing the dawn with his young cast.

“Oh, yes. What a time. I remember in 2023, I was fresh in my first Star Cinema project, which happened out of the blue. Suddenly, I started becoming a director for one of the biggest mainstream studios in the country. And then, the shock of my life, I was offered a project with one of their biggest stars, Kathryn (Bernardo), and also to be told that the timeline would also be the same as the timeline of Some Nights. “

He narrates, “The good thing about these two projects is that in Some Nights, all of our shooting days are reverse call. We start at 5 PM and we would end when the sun rises, and we would be able to shoot with daylight. I had literally days where, during the daytime, I would shoot A Very Good Girl, and I would wrap that around 5–6 PM, and then run to the set of Some Nights I Feel Like Walking.”

The balancing act didn’t scare him, it only affirmed his refusal to compartmentalize. “The directors I love just do what they want at that moment in time. If it feels true, then they do it,” he says. That freedom is messy, fearless, restless and is where Vargas thrives.

“Siguro it was because I spent so many years on this project, I felt like I knew the story and all the characters and the world that we built, that kahit nakapikit ako, kahit natutulog ako, aandar siya. So, that’s why it felt like on set, it was a kind of project where nothing wrong really happens. Like, I feel like parang nagfi-fit lang talaga the pieces of the puzzle.”

And the puzzle took a well-equipped village to form and put together. “It’s a combination of Philippines, Singapore, and Taiwanese. I got to work with friends from outside—so the cinematographer of Some Nights was Singaporean, the people who did sound design and sound mixing, excellent work, were from Taiwan. We were also produced by Anthony Chen, one of the biggest names in Southeast Asia. So, there’s that Southeast Asian collaboration.”

“The idea na ang daming tumutulong sa’yo to tell this singular story, it kind of lets you feel that this kind of story matters. Before nga, I was feeling like, valid ba talaga magkuwento ng stories of cruising, or everybody’s nocturnal encounters, that even at your friends at a party, you wouldn’t be so confident to share? [And] here I am, pitching to the whole world: this is how I discovered my full queer identity. Hinuhubaran ko talaga yung sarili ko, in the same way na naghubad yung mga characters sa pelikula. (laughs). Binigay ko talaga lahat.”

But going beyond what happened during those nights, this film eclipses topics that are often suppressed, those that are mouthed under the breath or left hanging in between pauses.

“I always love and I have a deep passion for being a part of stories like this. Stories that we know exist in the periphery but we just, most of the time, don’t choose to talk about kasi it makes people feel uncomfortable,” Alejandrino shares as he talks about the experience of portraying his character. As the film marries Filipino lived experiences with queerness, he echoes what they are hopeful for, and it is for people to find themselves through the lens of any of the boys.

Odron elaborates, “It’s a story of the Filipino condition, and these five boys, these orphaned kids take the brunt of everything that all of us, Filipinos, suffer.” Despite depicting a place like Manila where thousands of stories live through the day and night, the film ventures into spaces that are rarely visited— spaces that shelter “unspoken experiences” and “underbelly” stories that unravel at the deep recesses of a city that’s as widely exposed as it is closed up. And it gives us these glimpses through the lives of five young men who find meaning through each other.

And yes, queerness remains the overarching theme of the story. It is the element that bounded these boys, the fragment that threads their stories together. As Odron mentioned, “Queerness is the mother, the parents that these boys never had.”

“Films are very powerful. I know what it’s like to be in the cinema and watch a movie and then feel like my life changed after watching the movie,” Alejandrino shares.

Beneath all the craft lies a conviction: queer stories must multiply. To Vargas, films are more than cultural products; they are time capsules, preserving lived struggles and fleeting joys. He invokes The Celluloid Closet, the seminal text on queer cinema, to remind us that no single film can or should claim to represent queerness. Every narrative is a shard, a fragment of the collective. His own may speak of Manila nights and queer awakenings, but his friends, peers, and future filmmakers will add their transition stories, different loves, other kinds of survival. Together, they form the constellation.

“Oo, madami na pero damihan pa natin,” Vargas declares.

“Sabi nila, the birthing of representation is not entitled or enlisted to just one work, it’s the collective work of several filmmakers who were trying to make their own stories. Kasi iba yung lived experience ko as a queer gay guy du’n sa experience ng friend ko na kahit gay guy siya, iba yung coming out niya, iba siya magmahal, iba siya makipag-sex. And then, iba pa yung mga friends ko na nag-transition eventually, ’di ba, at nag-iidentify as trans, and now they have their own stories to tell.”

Some Nights I Feel Like Walking exists more than as a film, it is the ache of discovering a place you thought could never exist. It takes the rawness of Manila’s nights, where nothing is certain and nothing is owned, except the fragile safety of holding on to each other. Beneath the shadows and the silences, the film uncovers tenderness: chosen families built from strangers, fleeting bonds that somehow feel eternal. It listens to the unsaid, to the weight of bodies that belong nowhere, and dares to ask if, in walking together, one might stumble into something like home. It is a reminder that even in a world that shoves people to the margins, there will always be corners where you are seen, where your story matters, where existence itself becomes belonging. Few films leave you this vulnerable, this recognized, and this alive.

The film asks what it means to belong in a place that keeps telling you that you don’t. And in the quiet walk of grief, of brotherhood, of fleeting love, it confronts us with the haunting truth: that even one life lost is already too many. This is a film that doesn’t just want to be watched, it demands to be felt.

Vargas only hopes audiences will meet his work halfway. That Some Nights I Feel Like Walking lingers beyond its well attended screenings. That viewers carry with them the gravity of one story, one night, one body and understand how much is taken when even a single life is lost. Because some nights, cinema is not an escape. It is a witness. It is resistance. It is Petersen Vargas, still walking.

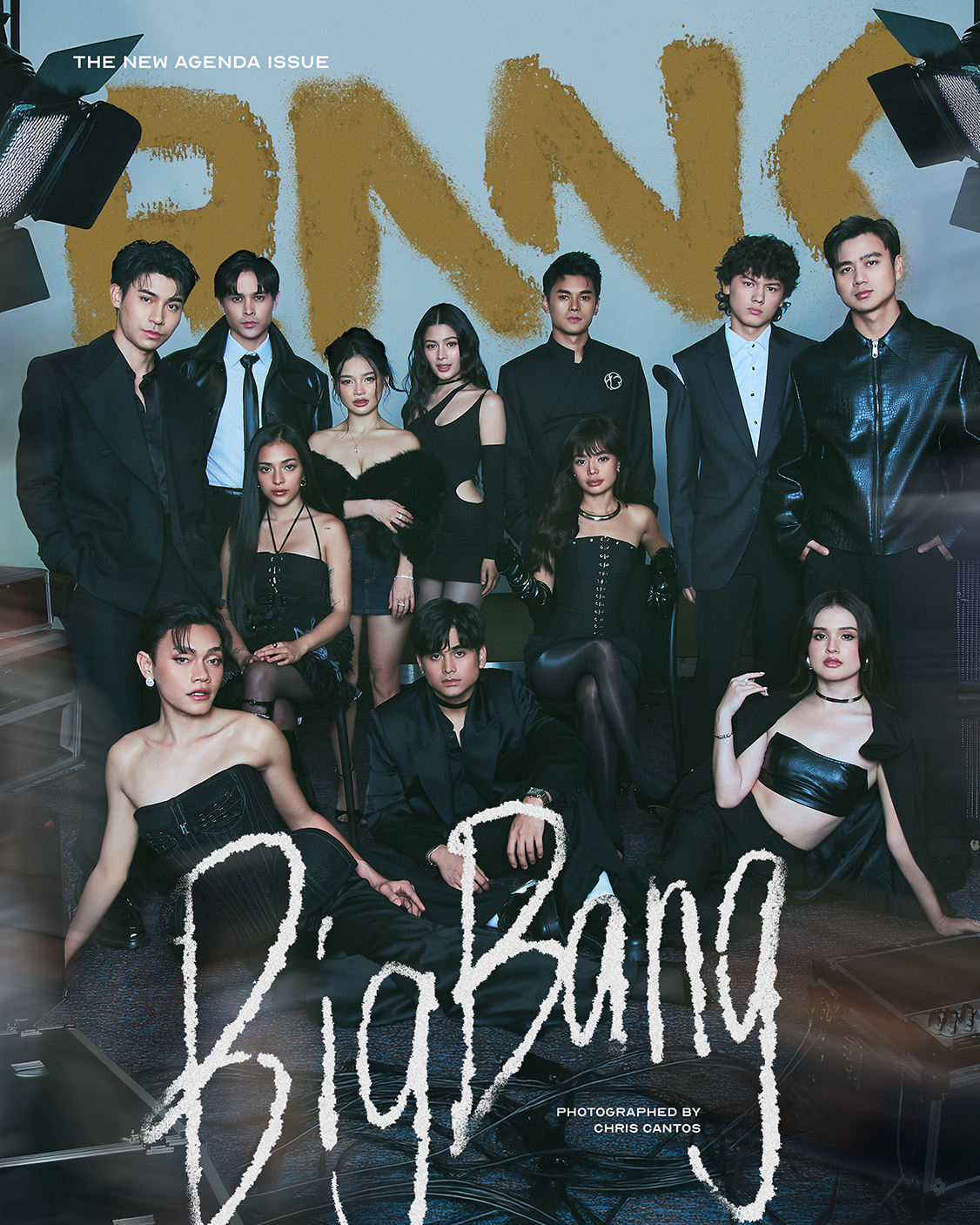

Produced by Rank Magazine

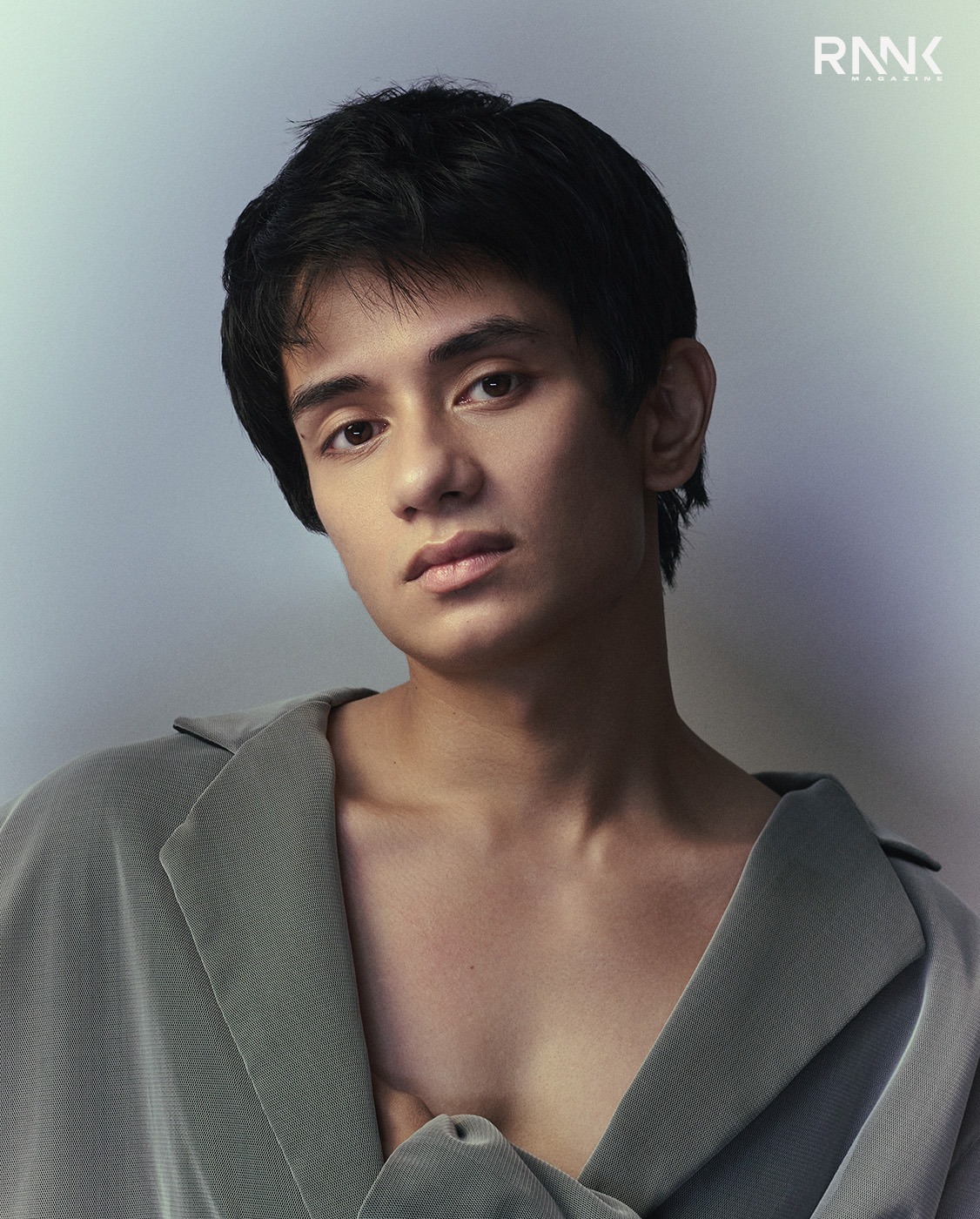

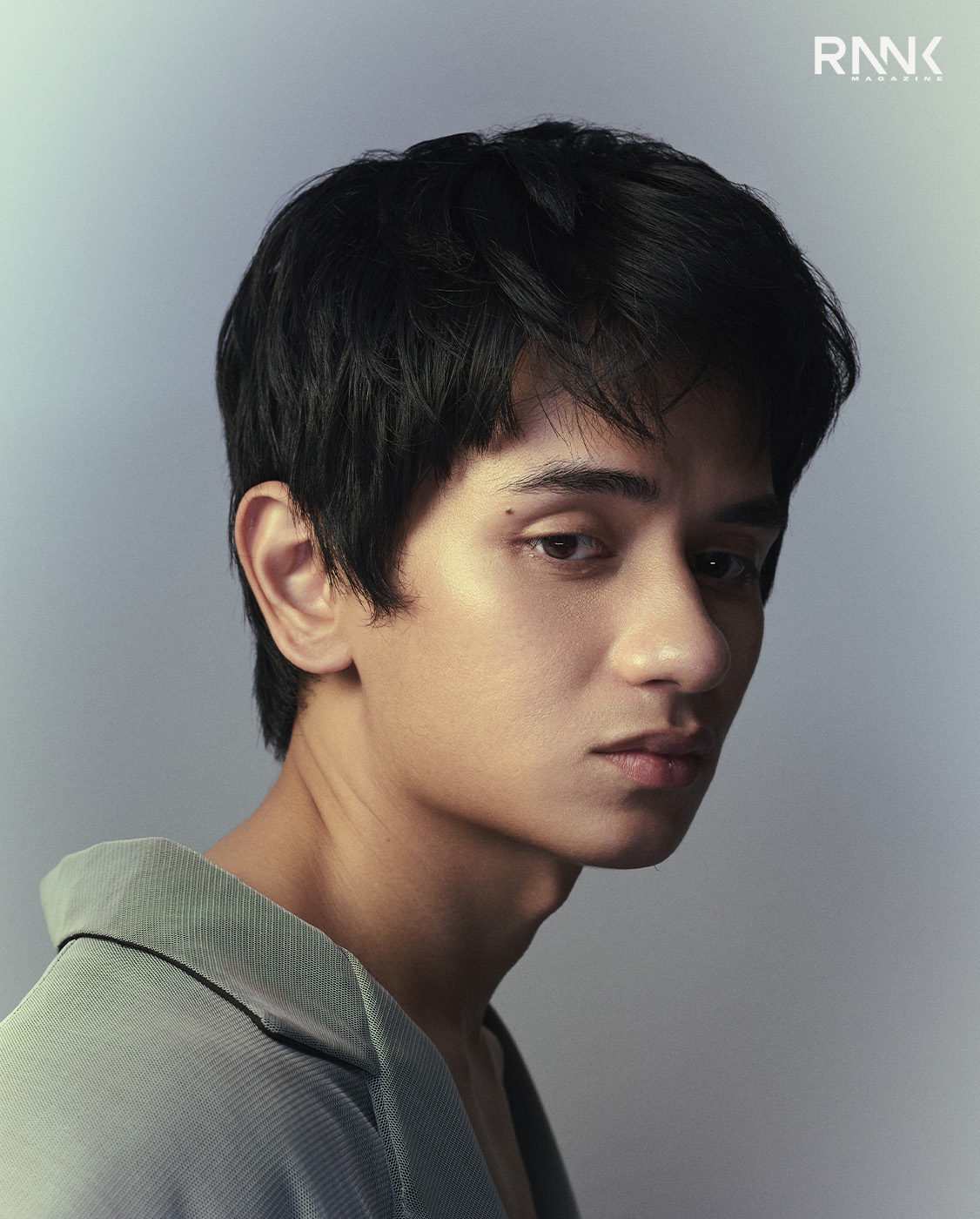

Creative & fashion direction, styling, interview and additional text by Leo Balante

Photography by Chris Cantos

Assisted by Niño Manalo

Hair & make-up by Lars Cabanacan

Multimedia manager: Bhernn Saenz

Multimedia associate: Czairus James Ronquillo

With fashion from Proudrace, Nina Amoncio, Ha.Mu Studios,Blanc Nue, and Randolf

Shot on location at the Holiday Inn Express Manila Newport World Resorts

With acknowledgments to Elpidio Beloso, General Manager at Holiday Inn Express Manila Newport World Resorts; Kathy Mercado, Senior Vice President, Commercial Sales; Arthur San Juan, Manager, Commercial Sales at Newport World Resorts

Special thanks to Petersen Vargas, Jericho Rimando, Kylechandler Bigay, and Carl Chavez at Lunchbox