Two films from the inaugural CineSilip Film Festival—Rodina Singh’s Dreamboi and Mikko Baldoza’s Haplos sa Hangin—have hogged social media headlines and reignited long-standing debates over censorship and creative freedom in Philippine cinema. Both films, described by the festival as “daring” and “unafraid,” were initially given X ratings by the government agency, Movie and Television Review and Classification Board (MTRCB), a classification that bans public exhibition.

For Singh, the rejection was deeply personal.

Dreamboi follows Diwa, a trans woman navigating fantasy, shame, and longing. “Dreamboi is not pornography; it is a story about being seen, about the pain and beauty of longing when the world tells you you’re not allowed to want,” said Singh in her post following the X Rating given to them by MTRCB. The film was rated X twice before finally being granted an R-18 classification just a day before the festival’s opening.

Haplos sa Hangin, directed by Baldoza, tells the story of a visual artist’s growing obsession with his neighbor trapped in an abusive relationship. It was also initially rated X, along with its poster, before eventually being re-classified as R-18 two days before the first day of the festival.

The controversy surrounding these decisions has once again exposed a familiar tension between protection and repression, raising the question of whether the MTRCB’s brand of morality still serves the evolving realities of Philippine cinema.

The bold and the beautiful

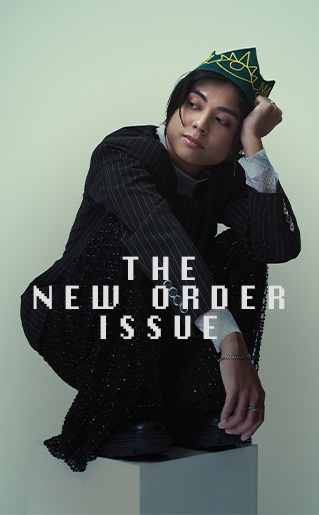

When VIVA Entertainment launched CineSilip in partnership with Ayala Malls Cinemas, from the company’s daring, adult-oriented app, VMX, the idea was to create a platform for stories rarely given space in mainstream theaters. Running from October 22 to 28, 2025, the festival’s title—“CineSilip,” or “to peek”—promised a look into the hidden and the unspoken, from sexual desire to personal liberation.

The lineup featured seven films by emerging filmmakers, including Dreamboi and Haplos sa Hangin. Festival director Ronald Arguelles described the showcase as “mapangahas, matapang, at naiiba”. It is a deliberate step toward giving voice to artists who challenge form and convention.

But even before the festival opened, that spirit of openness met resistance. The MTRCB’s X ratings for Dreamboi and Haplos sa Hangin threatened to overshadow what was meant to be a celebration of creative risk-taking.

The situation felt ironic. A festival created to encourage boldness was being met by an institution still guided by moral caution. CineSilip, envisioned as a space for artistic honesty, instead, became the latest battleground for a long and uneasy relationship between filmmakers and the state agency tasked to “classify” their work.

Films that tested the limits

What set Dreamboi and Haplos sa Hangin apart from the rest of the festival lineup was not only their subject matter but how quickly they exposed the limits of what the government agency considers viewable. Both films center on desire and the body, and both were made by filmmakers intent on showing the emotional truth behind intimacy rather than spectacle.

The MTRCB gave Dreamboi two successive X ratings before finally approving it with an R-18 classification a day before opening. In its official remarks, the board wrote that “while it offers important representation and commentary, its prolonged sexually explicit scenes make it inappropriate for public viewing.”

For Singh, the decision was a setback to what she described as a story that sought to humanize trans experience. She maintained that the film is “about being seen, about the pain and beauty of longing when the world tells you you’re not allowed to want,” insisting that it was never meant to provoke but to portray desire as part of human survival.

Meanwhile, Haplos sa Hangin faced a similar ordeal when both its film and promotional poster were initially denied approval. After revisions, it secured an R-18 rating, allowing it to be screened.

Arden Rod Condez, filmmaker behind the awarded Cinemalaya film John Denver Trending and among the producers of the film’s Southern Lantern Studios, simply posted on X (formerly Twitter), “Finally, we are R-18! Clutch gaming but now theater-ready.”

While both films were ultimately cleared for screening, the controversy highlighted how thin the line remains between artistic freedom and moral restriction. To many in the film community, the issue was not the rating itself but the lack of clear criteria and consistency, which continues to leave filmmakers guessing where creativity ends and censorship begins.

When ‘agency’ seems to be the hardest word

The X ratings drew immediate reactions from within the film industry and from audiences online, creating a chorus of frustration toward what many saw as outdated censorship.

Filmmaker Tonet Jadaone, behind the critical and box office success of recent film Sunshine, was among the first to speak up. In a statement posted online, she shared her support for the film and its director, describing the filmmaker’s persistence as an act of courage. “Dalawang beses na itong na-X. Nung pangalawang X, tumawag siya’t umiiyak. Pagod na si anteh ko. Pero for one hour lang. Bangon na uli, edit na uli. Ilalaban niya ito. Kasi kwento niya ito. Danas niya ito,” she wrote.

Jadaone argued that the film’s value lay in its honesty, not in its supposed indecency. “Dreamboi is not pornography. I have seen the scene in question, and it’s a moving, messy, beautiful exploration of trans desire,” she said. For her, the MTRCB’s refusal to grant clearance earlier reflected how the institution still confuses visibility with obscenity.

The UP Cinema released a separate statement condemning the censorship. It called the X rating a direct suppression of queer expression and said that marking queer bodies as obscene erases experiences that deserve to be understood. The group wrote, “Ang sensura ay hindi proteksyon. Isa itong tahasang pagkitil sa kalayaang malikhaing dapat ay ipinaglalaban ng ating industriya.”

UP Cinema also emphasized that Dreamboi is not pornography but a study of how desire becomes a means of healing and self-acceptance. Its statement ended with a call to action: “Walang tunay na sining kung may sensura. Walang tunay na kalayaan kung may pagpatahimik.”

Outside the film community, the response was even louder.

Online users criticized the MTRCB for what they saw as inconsistent and moralistic standards. One comment went the lengths of saying, “Abolish MTRCB,” echoed by many. Another said, “Need i-restructure at gawing clear yung guidelines. Hindi dapat depende sa beliefs ng current chairman.”

Some users warned that giving the agency more authority could affect streaming content, writing that, “this is the reason why MTRCB should be hands off with online streaming sites. Otherwise, almost all content with provocative subjects will be censored.”

Do we still need the MTRCB?

The wave of reactions from filmmakers, institutions, and the public made one thing clear. The issue had grown beyond Dreamboi and Haplos sa Hangin. It had become a conversation about the role of authority in art, and about how one government body continues to decide what audiences can or cannot see. In an industry that constantly redefines itself through new voices and platforms, the question returns with more urgency. Do we still need the MTRCB?

The country’s media landscape has changed completely. Viewers today have access to a global library of films and series that portray sexuality, violence, and identity in ways that challenge long-held moral boundaries. Streaming platforms already issue their own advisories and age restrictions, leaving the MTRCB’s control limited mostly to local theaters and television. For many, this makes the board’s presence feel increasingly outdated in a system where audiences already have the power to choose for themselves.

Supporters of the agency argue that it remains necessary to protect minors and preserve community standards. Critics, however, point out that its lack of consistent guidelines and transparency often results in arbitrary decisions that stifle creativity rather than protect it.

Both Dreamboi and Haplos sa Hangin were made for mature audiences and both sought to engage with desire as a human experience. Yet the board’s handling of their ratings revealed how creative work can still be judged not for what it says, but for how uncomfortable it makes those in power feel. What should have been a classification process turned into a gatekeeping exercise that forced artists to edit, justify, and plead for their stories to be seen.

Filmmakers and institutions have long called for reform. Their demand is simple—clarity, transparency, and a willingness to engage with creators instead of policing them. Many believe that consultation and context must replace the instinct to ban. Regulation should not be about silencing difficult subjects but about helping audiences approach them responsibly.

If the MTRCB’s purpose is to protect, then real protection should mean trust. Trusting artists to tell stories with honesty and trusting audiences to think critically about what they see. Because when visibility continues to be treated as danger, the most dangerous thing left is not the art itself, but the silence that follows when it is kept from view.